TAIPANS NUMBER ONE ...

Beyond Their bite, these snakes are like other Australian

elapids.

Raymond Hoser

adder@smuggled.com

Originally

Published in Reptiles (USA), August 2008.

Perhaps the worst snake to be bitten by

is the taipan (Oxyuranus spp.). Even

with advent of antivenom the prognosis for survival from a bite isn't good.

Experiments with mice show an average taipan bite is potent enough to kill

about 50,000 mice or 50 people. They’re considered the world’s deadliest

snakes, and snakekeepers everywhere covet them.

Perhaps the worst snake to be bitten by

is the taipan (Oxyuranus spp.). Even

with advent of antivenom the prognosis for survival from a bite isn't good.

Experiments with mice show an average taipan bite is potent enough to kill

about 50,000 mice or 50 people. They’re considered the world’s deadliest

snakes, and snakekeepers everywhere covet them.

But getting past taipans deadly

number-one status, what really separates these snakes from other Australian

elapids? The reality is not all that much.

Brown, Jumpy and Adaptable

Taipans are large and thin snakes. Mature males average 210 cm in total length, and females measure 180 cm. Most are brownish.

With large eyes, they’re generally

presumed to be one of the most intelligent snakes because they rely to a

greater extent on both sight and smell to detect objects rather than

essentially just smell like many other snakes.

Brown snakes (Pseudonaja spp.)

and taipans are unusual among Australian snakes because their bellies are

yellowish and sport distinct flecks or squiggles, especially on the

forebody. Other “brown” snakes from the

genera Cannia, Panacedechis and Pailsus

lack this trait.

Currently there are three named taipan

species: Oxyuranus scutellatus, O. microlepidota and O. temporalis.

Although taipans are deadly, they would rather run away than fight or bite.

They can move backwards at high speed and thus have a good “reverse gear.”

Unless you try to catch or kill a

taipan, the risk of bite is slight. Remember, these snakes should only be

caught or handled by people with experience in handling deadly snakes. Even

experienced handlers must be prepared to risk the consequences of an unexpected

bite (i.e. death).

More often than most snakes, taipans

will flick their body or "jump" when approached or touched. This behavior instills fear in the handler

and may be a precursor to a bite. However, this isn’t always the case.

Sometimes the rapid flick is mistaken for aggression when it's not.

In the wild taipans are like most other

large diurnal elapids. They are adaptable to various habitats so long as their

basic requirements are met. These include shelter, a basking spot for warmth

and proximity to a water source. They like a drink every two days or so.

Wild taipans seem to prefer rodents,

but smaller members will eat lizards and rarely frogs. These snakes’ partiality

to rodents as opposed to frogs has given them a recent relative advantage and

numbers increase over competitors such as red-bellied black snakes (Pseudechis porphyriacus) and Papuan

blacks (Cannia papuanus). Both prefer

frogs, and many have died trying to eat cane toads (Rhinella marina,

formerly known as Bufo marinus),

which produce a toxin for self-defense.

Taipans may actively run down their

prey. This gives you an idea as to how

fast they can move. They are also “ambush” predators that wait under cover for

food items to pass.

Keeping Taipans

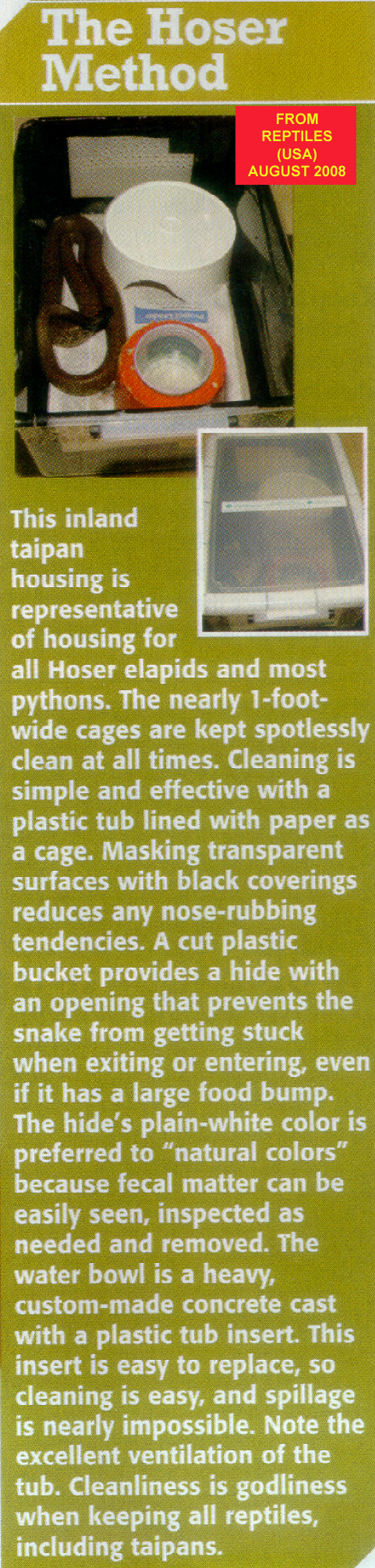

Snakekeepers should keep taipans like

any other elapid. I keep my 2-meter-long adults in 60 cm plastic tubs in a rack

system. They don’t nose rub, which is the most obvious sign a cage is too

small, so I assume the space suits them. I don’t change cage size according to

age, but larger snakes go in larger cages.

If snakes do rub their snouts, enlarge

the cage, reduce the number of transparent surfaces or both. Although snout

rubbing has been seen in other elapids, such as copperheads (Austrelaps spp.),

I have not seen it in my taipans, and reports of it are rare.

Provide the snakes with a basking area

of about 30 to 35 degrees C, and aim for a cooler refuge of about 20 degrees C

but allow for anything between 10 to 26 degrees depending on seasons and other

factors. Also provide a hide and a water dish. Captive taipans never swim — not

that I’ve seen anyway — so the size of the water container need not be huge,

but it should be deep and not spill. Other cage accessories are optional.

In terms of cage access, you need to be aware of bite risks and plan accordingly. Taipans can be agreeable, but even so, it is not uncommon for me to see snakes kept in standard top-opening cages lunge out to strike their owner every time the cage is opened.

Coastal taipans (Oxyuranus

scutellatus) and inland taipans (O. microlepidota) are found in

similar numbers in captivity. In terms of demeanor, O. microlepidota is

the more civilized species. For the most part it's unusual to have an

aggressive inland taipan. Juveniles or wild snakes when they’re first caught

are the exceptions. Aggressive coastal taipans seem common, especially if they

are wild caught or mishandled.

They’re Intelligent. Are You?

Captive taipans roam about their cages

and generally are active and alert. They show their relative intelligence by

recognizing different handlers and reacting differently to them.

Wild-caught specimens start out

aggressive (most likely because of fear) and will bite if given a chance.

However, a taipan’s intelligence actually works in its favor under captive

conditions. The snakes tend to settle down within weeks. More intractable ones

may take a few months. Taipans remaining "aggressive" beyond this

time are usually exposed to improper management or bad handling.

Keeping and handling venomous snakes

requires skill, but this expertise isn't just necessary to avoid a bite. It

also includes being able to handle a snake so it has no fear of its handler and

thus loses all inclination to bite.

Snakekeepers should avoid startling their

taipans when opening up cages, and they should avoid aggressively pinning

snakes or doing much else that may cause pain, stress or reason to bite. These

snakes have plenty of strength and ability to squirm if “necked,” grabbed by

the neck in a pincerlike or grabbing-type restraining hold, and handlers should

be aware of this before attempting such a move.

Taipans adapt to being handled with a hook quite quickly, and most keepers soon find the day-to-day keeping and moving of the snakes to be quite easy.

Food for Deadly Fangs

As a rule, feed rodents to taipans from

the time they hatch, and merely up the size as the snakes get bigger. Although

elapids cannot distend their mouth and jaws as wide as pythons, taipans can do

so to a greater degree than any other Australian elapid. Hence a rodent’s size

can be slightly greater than the width of an unfed snake but no larger.

Besides rodents, I have fed my larger

taipans other food items without apparent ill-effects to the snakes. These

include lumps of meat, fish and chicken necks.

Hatchlings and smaller snakes often

don't feed voluntarily, especially if live food is unavailable, so

force-feeding very young taipans is routine at my facility. A common mistake of

elapidkeepers is to try to get their snakes to voluntarily feed, but the result

is that snakes get too emaciated to recover before force-feeding begins, or

they starve to death.

Taipans pull back when pinned near the

head or neck, in a “retract response”, which is essentially a defensive move.

This habit makes young snakes easy to pin and neck in order to force-feed them.

Always be wary of their fangs. In the absence of voluntary feeding I force-feed

hatchlings dead mice every few days, including when they’re eyes are clouded,

until they grow to about 60 cm (about 5 months old). Then they are assist-fed

and eat readily.

Usually about one to three months later

the snakes commence voluntary feeding on whatever you have been feeding them.

In my case this includes mouse legs, lumps of beef and chicken, and fish.

Adult Taipans are usually voracious. It

is unlikely to have one that doesn't feed voluntarily — even on dead food —

unless it's very sick.

Compared to other large Australian

elapids, taipans pass food considerably slower. For example, brown snakes (Pseudonaja spp.) under 24-hour heat may

take 24 hours to digest a mouse. Taipans under similar conditions may take two

to three days to pass the same size mouse. Only death adders (Acanthophis spp.) have slower digestive

rates, which may have something to do with their being ambush predators.

Breeding Oxyuranus

Breed taipans like you would for most

other snakes. Separate the sexes and cool for "winter." There is no

compelling need to keep seasons in line with either the northern or southern

hemisphere. Even at our facility in Australia we run our “seasons” about four

months ahead of the natural cycle.

Contrary to what many people say, in most parts of Australia, including north Queensland, taipans hibernate as much as they are inactive during the winter months. In the wild their activity ceases at the end of the northern wet fall season (April/May), and they don't become active again until about late winter (August). Activity peaks a month or two later in spring.

In captivity, breeding success is

achieved by keeping taipans under 20 degrees C, but a diurnal temperature range

between 14 and 20 degrees C is best. Photoperiod does not seem terribly

relevant as the movement of snakes in their cages seems mainly temperature

dependent and it is temperature that regulates breeding cycles. Notwithstanding light coming through windows

and my own activity in the snake’s room, room lights tend to run 12 hours a day

all year due to the fact that not all snakes in the room may necessarily be in

“hibernation mode”. Run the “winter” period for about seven weeks minimum. Then

increase the temperature at the warm end of the cage to 30 degrees for another

12 weeks with 12 hours of heat. One part of the cage should remain at 20

degrees C (or thereabouts) at all times.

Introduce males and females at the end

of this period, and as a matter of course most males mount the females

immediately. Connection usually ensues within 12 hours and generally lasts 12

to 20 hours. More than one successful mating in succession, such as two to three

during the course of a month, increases chances of a female developing fertile

eggs.

In a recent world first, Snakebusters

engaged in artificial (or assisted) insemination for various squamates,

including taipans. We collected semen from males and transferred it via

straight glass capillary tubes into female snakes. The process was developed

for specific snakes that were fertile but didn’t mate, but it has since been

expanded to enable mating of snakes in different facilities without the need to

transport animals or do breeding loans. Although some of these inseminations

produced young, the taipans weren’t among them. The world first was successful

artificial insemination in numerous species of squamates using a single

technioque to produce healthy offspring, including Tiger Snakes and

Bluetongues. The latter is important as

the Adelaide Zoo has not been able to breed the endangered Tiliqua

adelaidensis using “natural” means.

Most snake breeders will do well with

just one male taipan. It's rare to have a dud, and males engage in combat

during the mating season.

To incubate eggs, the standard 30

degrees at 100 percent humidity works fine. Do not supersaturate the eggs, or

they will sweat and go off. If the incubation medium, such as coarse-grade

vermiculite, appears too wet, add more dry vermiculite to the mix.

Rearing Danger

For the 2004-2005 season statistics for

my coastal taipans were as follows. Eggs were laid in December 2004. Eighty

percent covered in vermiculite, they were incubated between 28.5 and 30.5

degrees C at 100 percent humidity. They hatched in February 2005 after 77 days.

Young averaged 36 cm in total length, and they passed 60 cm in June 2005. Kept

as warm as they could tolerate (they straddled their heat mat), they were fed

as much as they could eat.

A growth rate of about 5 cm a month is

about as good as one can get for taipans. This is far lower than some growth

rates quoted in literature, and some of these rates could be exaggerated,

mismeasured or amazingly freakish. However, short-term growth rates of 10 cm

per month are definitely possible.

Young taipans of both species kept in

captivity are known to drop dead suddenly and without obvious explanation.

Outside of these cases, the snakes are not particularly difficult to

raise.

Males and females have similar growth

rates. Females are generally more slender in build, including their heads. They

are also usually more placid than males, which is the trend seen in most

Australian elapids where males engage in combat. Although it is possible to

accurately guess the sex of adult taipans based on their builds or relative

tail thickness (tail sexing), probing is the only reliable way to sex these

snakes.

Although drably colored, taipans aren’t

particularly aggressive by snake standards, and their general intelligence and

number-one status in venom potency/yield makes them a welcome addition to a

collection of deadly snakes.

SIDEBAR A

SIDEBAR 1

Battle of the Browns

Historically, taipans were found across

most of Australia and New Guinea until probably within the past 30,000 years.

This included most of the northern two-thirds of continental Australia. At some

recent time, king brown snakes (Cannia

spp.) or their precursors moved across northern Australia and literally

outcompeted taipans and other species of similar size. The end result has been

a general contraction in the taipan’s range. In modern times these snakes are

scarce or extinct where king browns are common, which helps explain the

disjunct distribution of taipans across most parts of northern Australia except

the Queensland coast, where king brown snakes are generally absent and taipans

are common.

SIDEBAR 2

Indonesian Exports

Taipans are native to Australia, but a

reovirus has adversely affected snakes in Australian collections. It has led to

a shortage in the country. In the United States, taipans are imported from

Irian Jaya, Indonesia. The best place for people living outside Australia to

get these snakes is from Indonesian-based exporters. Most specimens are shipped

from Merauke, and they come from the immediate vicinity. Assuming legal and

safety hurdles are covered, the snakes aren’t too expensive to obtain.

SIDEBAR 3

Watch the Fangs

Snakekeepers force-feeding taipans food

or medicine should always be wary of the fangs. These snakes sport 1.5 cm long

fangs and large venom glands (by Aussie standards anyway). Taipan fangs tend to

flex somewhat, so they may move slightly and accidently prick and envenomate an

unsuspecting handler. Sometimes they even penetrate the snake’s lower jaw. These

fang characteristics make taipans more dangerous during necking than the

average elapid, and that's before you realize they are the deadliest snake on

earth.

SIDEBAR 4

Plagues on a Killer

Because so many taipans are

wild-caught, your new charge might have some health issues. Here are three

problems and their treatments.

- Taipans may carry ticks. If attached to a snake’s lower

jaw, they give it a bearded appearance. To treat for ticks (and also as a

secondary mite treatment) It is best to inject with ivermectin (at about

150% the dose rate for cattle by weight and after two ays, pick off any

dead ticks with tweezers. Use commercial mite sprays or appropriate pest

strips for “mite only” problems.

2. Tapeworms,

nematodes and lungworms are common in wild adults. Treat these parasites with

the usual drugs: Droncit (PO), Panacur (PO) and Ivermectin (IM). PO is “orally”

and “IM is intamuscular injection.

3. Skin lumps,

caused by an internal parasite migrating through the snake’s body and ending up

encysted under the skin, are also seen sometimes. Snakes eating infested skinks

(and occasionally other animals) encounter the problem. External lumps may be

literally “cut out” through incisions between scales, while the unseen internal

ones are heard to deal with. The use of

tapeworm treatments has a level of success.

ONLINE

Know Your Taipan

Currently there are three

named taipan species: Oxyuranus scutellatus, O. microlepidota

and O. temporalis. With its ghost-white snout and coffin-shaped

head, the coastal taipan (O. scutellatus)

is found along the coast of Queensland and nearby areas of Australia. However,

as one moves outside this range into northern New South Wales, the Northern

Territory or northwest Western Australia, populations are scattered and

scarce.

The species also occurs in New Guinea.

Two distinct races are found there. Coastal taipans from Irian Jaya and nearby

are essentially similar to the northern Australian animals. Those from east Papua

New Guinea, such as Port Moresby, are distinctly grayish-black. Known as O.

scutellatus canni, they often have orange coloring along the middorsal

line.

Coastal taipans from northwest

Australia (O. scutellatus

barringeri) are usually more reddish than their eastern cousins. But no

matter what their color, coastal taipans tend to darken during the winter.

The inland taipan (Oxyuranus microlepidota) varies in color, but it usually has a

darkish head and snout. Snakes from eastern Australia’s inland areas of black

soil and floodplains are usually brownish, but the color varies seasonally. The

darker winter color includes a blackish head.

These snakes are superficially similar

to some western brown snakes (Pseudonaja

nuchalis) found in the same areas. At a glance, it’s often impossible to

tell the two species apart. But taipans have 23 midbody rows, and brown snakes

have only 17 to 19.

Not much is known about the newly named

taxon Oxyuranus temporalis from inland Western Australia. The original

diagnosis for the species was weak and in parts erroneous, and it was based on

a single dead museum specimen. The snake is similar in many respects to O.

scutellatus.

Non-urgent email inquiries via the Snakebusters bookings page at:

http://www.snakebusters.com.au/sbsboo1.htm

Urgent inquiries phone:

Melbourne, Victoria, Australia:

(03) 9812 3322 or 0412 777 211

© Australia's Snake Man Raymond Hoser.

Snake Man®, Snakebusters®, and trading phrases including: Australia's BEST reptiles®, Hands on reptiles®, Hold the Animals®, and variants are registered trademarks owned by Snake Man Raymond Hoser, for which unauthorised use is not allowed. Snakebusters is independently rated Australia's BEST in the following areas of their reptile education business.